Last edited: Jul 1, 2020, 10:24pm -0600

Replication is bad for decentralized storage

This article was originally posted on the Storj Labs blog.

Hi! JT Olio here. We recently launched the white paper for our V3 network! The document offers 90 pages of detail about what we’ve built and are now working on for our near-term roadmap, and it’s wonderful to finally have it out!

I would have loved to go into this amount of detail during my conversation with David Vorick of Siacoin a few months ago. We were talking about how this V3 architecture is fundamentally better than other approaches, but I was unable to go into why at that time. Now, with the release of our white paper, we can finally dive into those reasons.

There are a number of potentially controversial claims our paper makes, and the claim that erasure codes are strictly better than replication over wide-area networks is one of them. I had a great conversation with David Irvine of MaidSafe about this section of our paper recently and thought it might be worth presenting our argument in a bit more conversational style here, on our blog.

Durability and expansion factor

In a decentralized storage network, any storage node could go offline permanently at any time. A storage network’s redundancy strategy must store data in a way that provides access with high probability, even though any given number of individual nodes may be in an offline state. To achieve a specific level of durability (defined as the probability that data remains available in the face of failures), many products in this space (Filecoin, MaidSafe, Siacoin, GFS, Ceph, IPFS, etc.) by default use replication, which means simply having multiple copies of the data stored on different nodes.

Unfortunately, replication anchors durability to the network expansion factor, which is the storage overhead for reliably storing data. If you want more durability, you need more copies. For every increase of durability you desire, you must spend another multiple of the data size in bandwidth when storing or repairing the data, as nodes churn in and out of the network.

For example, suppose your desired durability level requires a replication strategy that makes eight copies of the data. This yields an expansion factor of 8x, or 800%. This data then needs to be stored on the network, using bandwidth in the process. Thus, more replication results in more bandwidth usage for a fixed amount of data.

On the one hand, replication does make network maintenance simpler. If a node goes offline, only one of the other storage nodes is needed to bring a new replacement node into the fold. On the other hand, for every node that is added to the redundancy pool, 100% of the replicated data must be transferred.

Erasure Codes?

Erasure codes are another redundancy approach, and importantly, they do not tie durability to the expansion factor. You can tune your durability without increasing the overall network traffic!

Erasure codes are widely used in both distributed and peer-to-peer storage systems. While they are more complicated and possess trade-offs of their own, the scheme we adopt, Reed-Solomon, has been around since 1960 and is used everywhere from CDs, deep space communication, barcodes, advanced RAID-like applications—you name it.

An erasure code is often described by two numbers, \(k\) and \(n\). If a block of data is encoded with a \(k\), \(n\) erasure code, there are \(n\) total generated erasure shares, where only any \(k\) of them are required to recover the original block of data! It doesn’t matter if you recover all of the even numbered shares, all of the odd numbered shares, the first \(k\) shares, the last \(k\) shares, whatever. Any \(k\) shares can recover the original block.

If a block of data is \(s\) bytes large, each of the \(n\) erasure shares are roughly \(s/k\) bytes. For example, if a block is 10 MB, and you’re using a \(k = 10\), \(n = 20\) erasure code scheme, each erasure share of that block will only be 1 MB. This means that with \(k = 10\), \(n = 20\), the expansion factor is only 2x. For a 10 MB block, only 20 MB total is used, because there are twenty 1-MB shares. The same expansion factor holds with \(k = 20\), \(n = 40\), where there are forty 512-KB shares.

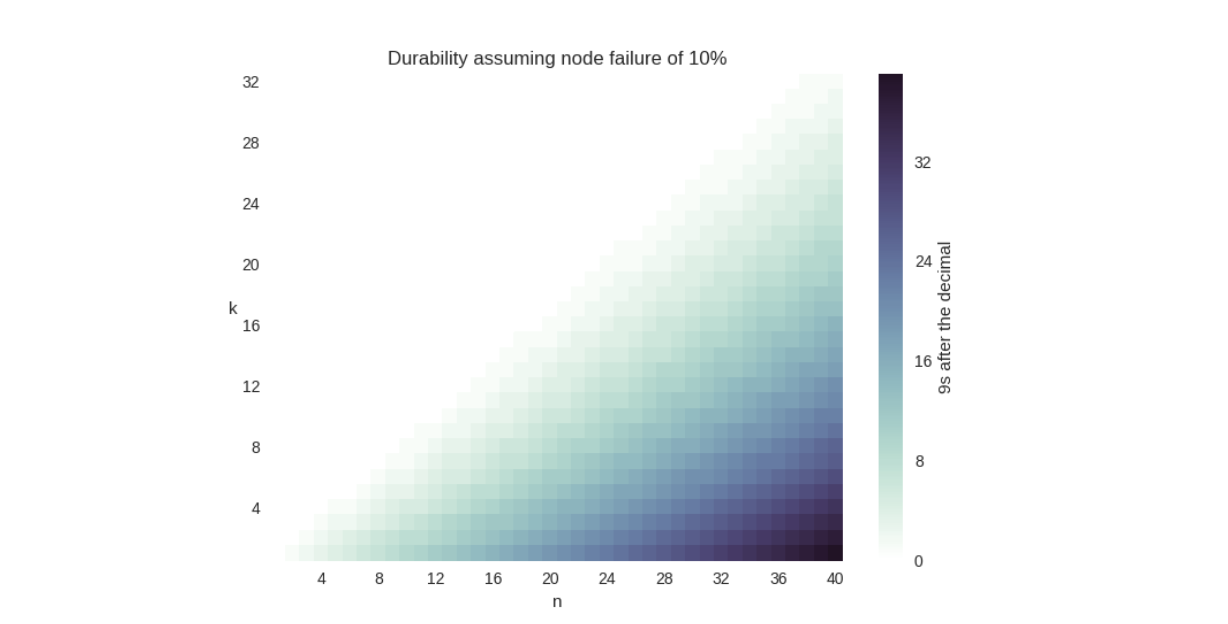

Interestingly, the durability of a \(k = 20\), \(n = 40\) erasure code is better than a \(k = 10\), \(n = 20\) erasure code, even though the expansion factor (2x) is the same for both. This is because the risk is spread across more nodes in the \(k = 20\), \(n = 40\) case. To help drive this point home, we calculated the durability for various erasure code configuration choices in a network with a churn of 10%. We talked more about the math behind this table in section 3.4 of our paper, and we’ll discuss more about churn in an upcoming blog post, but suffice it to say, we hope these calculated values are illustrative:

Notice how increasing the amount of storage nodes involved increases the amount of durability significantly (each new 9 is 10x more durable), without a change in the expansion factor. We also put this data together in a graph:

Admittedly, this graph is a little disingenuous: the chances of you caring about having thirty-two 9s of durability is… low, to say the least. The National Weather Service estimates the likelihood of you not getting hit by lightning this year at only six 9s after all. But you should still be able to see that a \(k = 2\), \(n = 4)) is less durable than a \(k = 16\), \(n = 32\) configuration.

In contrast, replication requires significantly higher expansion factors for the same durability. The following table shows durability with a replication scheme:

Comparing the two tables, notice that replicating data at 10x can’t beat erasure codes with \(k = 16\), \(n = 32\), which is an expansion factor of only two. For durable storage, erasure codes simply require ridiculously less disk space than replication.

If you want to learn more about how erasure codes work, you can read this introductory tutorial I co-wrote last year.

Okay, erasure codes take less disk space. But isn’t repairing data more expensive?

It’s true that replication makes repair simpler. Every time a node is lost, only one of the remaining nodes is necessary for recovery. On the flip side, erasure codes require several nodes to be involved for each repair. Though this feels like a problem, it’s actually not.

To understand why, let’s set up both scenarios, replication at 9x and erasure codes at \(k = 18\), \(n = 36\), and consider what it costs us. These numbers are chosen because they have similar durability (9x replication has six 9s of durability assuming 10% of node churn, and \(k = 18\), \(n = 36\) erasure coding has seven). We’ll consider what happens when we are storing a data block that is 18 MB and we suddenly lose one-third of our nodes.

At 9x, replication in our model of course has an expansion factor of 9. Once again, replication is the simplest to implement. If we lose one-third of our nine nodes we will need to spin up three new nodes. Each new node transfers a copy of the lost data, which means that each node must transfer 18 MB. That’s a total of 54 MB of bandwidth usage for repair. No intensive CPU processing was needed.

With \(k = 18\), \(n = 36\) erasure codes (with an expansion factor of only two), losing one-third of our nodes means we now only have 24 nodes still available and need to repair to twelve new nodes. The data each node is storing is only 1 MB each, but eighteen nodes must be contacted to rebuild the data. Let’s designate one of the nodes to rebuild the data. It will download eighteen 1 MB pieces, reconstruct the original file, then store the missing twelve 1 MB pieces on new nodes. If this designated node is one of the new nodes, we can avoid one of the transfers. The total overall bandwidth used is at most 30 MB, which is almost half of the replication scenario. This advantage in bandwidth savings becomes even wider with higher durabilities.

Downsides?

Erasure coding did require more CPU time, that’s true. Still, a reasonable erasure encoding library can generate encoded data at at least 650 MB/s, which is unlikely to be the major throughput bottleneck over a wide-area network with unreliable storage nodes.

Erasure coding also required a designated node to do the repair. While this complicates architectures in untrusted environments, it is not an unsolvable problem. It simply requires the addition of hashes, signatures, and retries in a few new places. This is something we’ll talk about more down the road. We have a lot of blog posts to write!

Notably, erasure coding does not complicate streaming. Remember how I said erasure codes are used for satellite communication and CDs? As long as erasure coding is batched into small operations, streaming continues to work just fine. See Figure 4.2 and sections 4.1.2 and 4.8 in our white paper for more details about how we can pull native video streaming off.

Upsides?

Comparing 9x replication and \(k = 18\), \(n = 36\) erasure coding, the latter uses less than half the overall bandwidth for repair. It also uses less than a third of the bandwidth for storage and takes up less than a third of the disk space. It is roughly ten times more durable! Holy crap!

Oh, and did I mention this also enables us to pay storage node operators more? Specifically over three times more? Because the disk-space usage is more efficient, there is more money available for each storage node operator. The income is less diluted across storage nodes, you could say.

It’s worth re-reading those last two paragraphs. These gains are significant. Hopefully by this point you’re convinced that erasure codes are better.

Stay Tuned

It gets worse for replication. Stay tuned for part 2, where we’ll talk about network churn and explain why replication-based schemes over wide-area networks may not even be capable of achieving S3-level durability. For a sneak peek, be sure to check out this research paper.

Until then, this is not the only controversial topic in our white paper. Read the rest and let us know what you think! We’ll be covering other white-paper topics on our blog here in the coming weeks. Also, feel free to join our waiting lists!